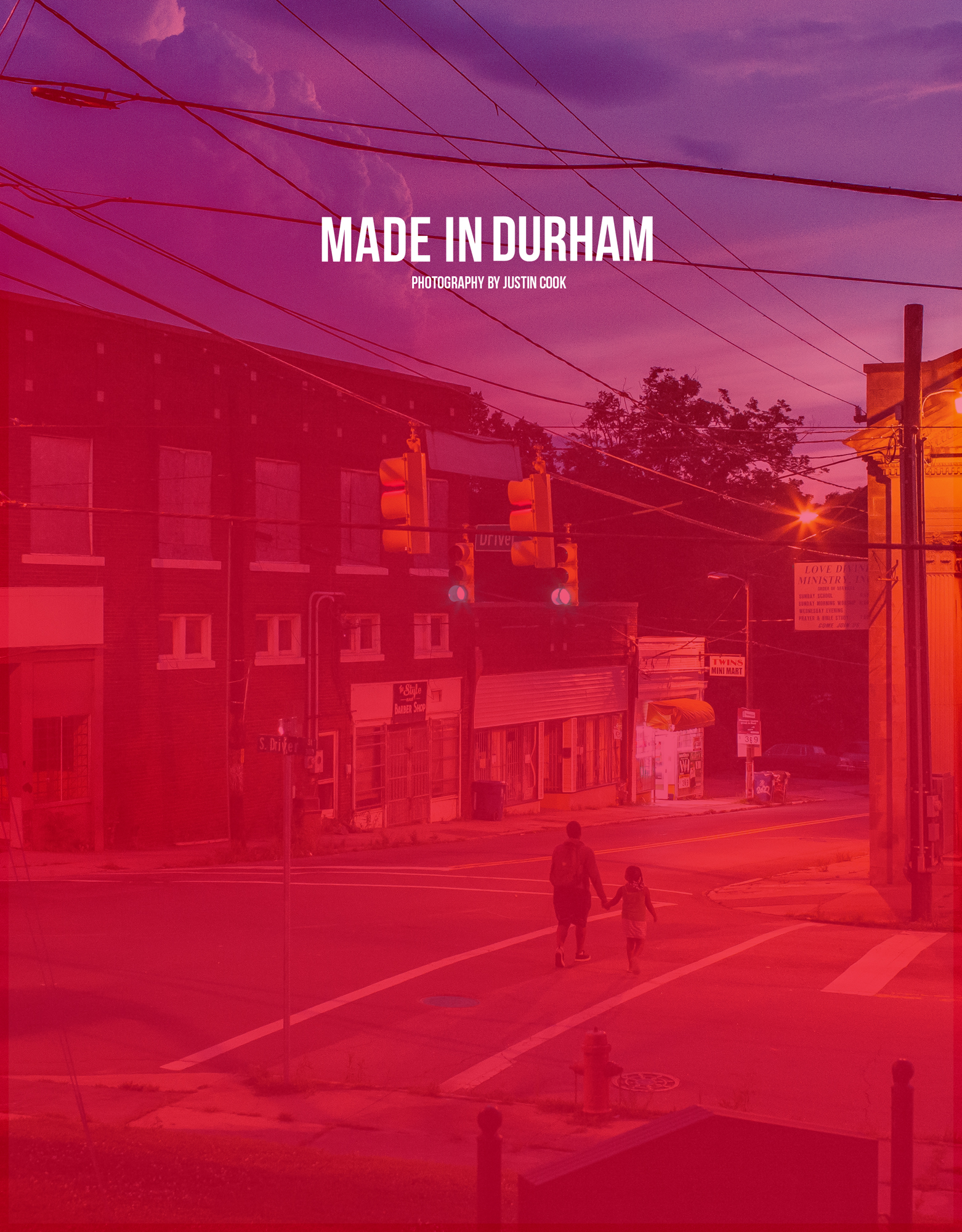

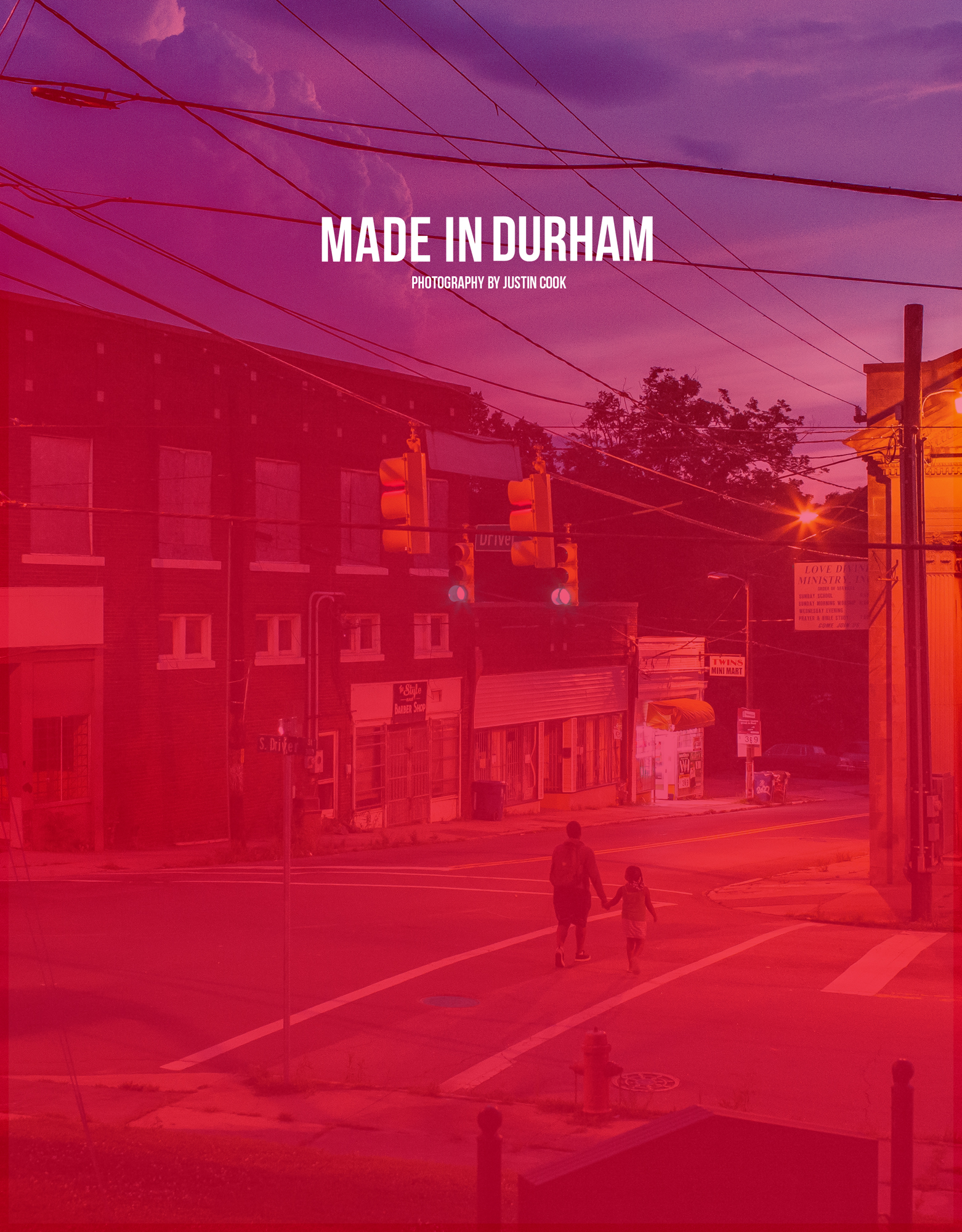

Made in Durham the zine, front cover.

Fireworks burst over the Durham Bulls Athletic Park in revitalized downtown Durham, N.C. on Independence Day, July 4, 2014.

A mural of Durham’s historic African-American Hayti Community at the Heritage Square shopping center is disintegrating. Older residents say Hayti was ruined in the 1960s and 1970s by urban renewal projects including the Durham Freeway, which cut off thriving black businesses from downtown. Others suggest that Hayti was already declining through unemployment and people leaving the neighborhood and that its demise was inevitable.

Kalin Swinney pauses by the casket of his first cousin, 9-year-old Jaeden Sharpe, at Beechwood Cemetery. Jaeden was shot in the head and his mother, in the face, as they sat in her car near their home on Jan. 4, 2014. He died Jan. 9. His murder was the first of 2014 in Durham. Nationally, the leading cause of death for black males ages 15 to 34 is homicide, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. From 2009 to 2012, Durham’s homicide rate for black males ages 15 to 34 was about eight times the national rate. Seventy-three percent of gun-homicide victims ages 15 to 34 were black; 3 percent were white. Eighty-three percent of gun-involved aggravated assault victims were black; 8 percent were white, according to an April 2015 U.S. Department of Justice report.

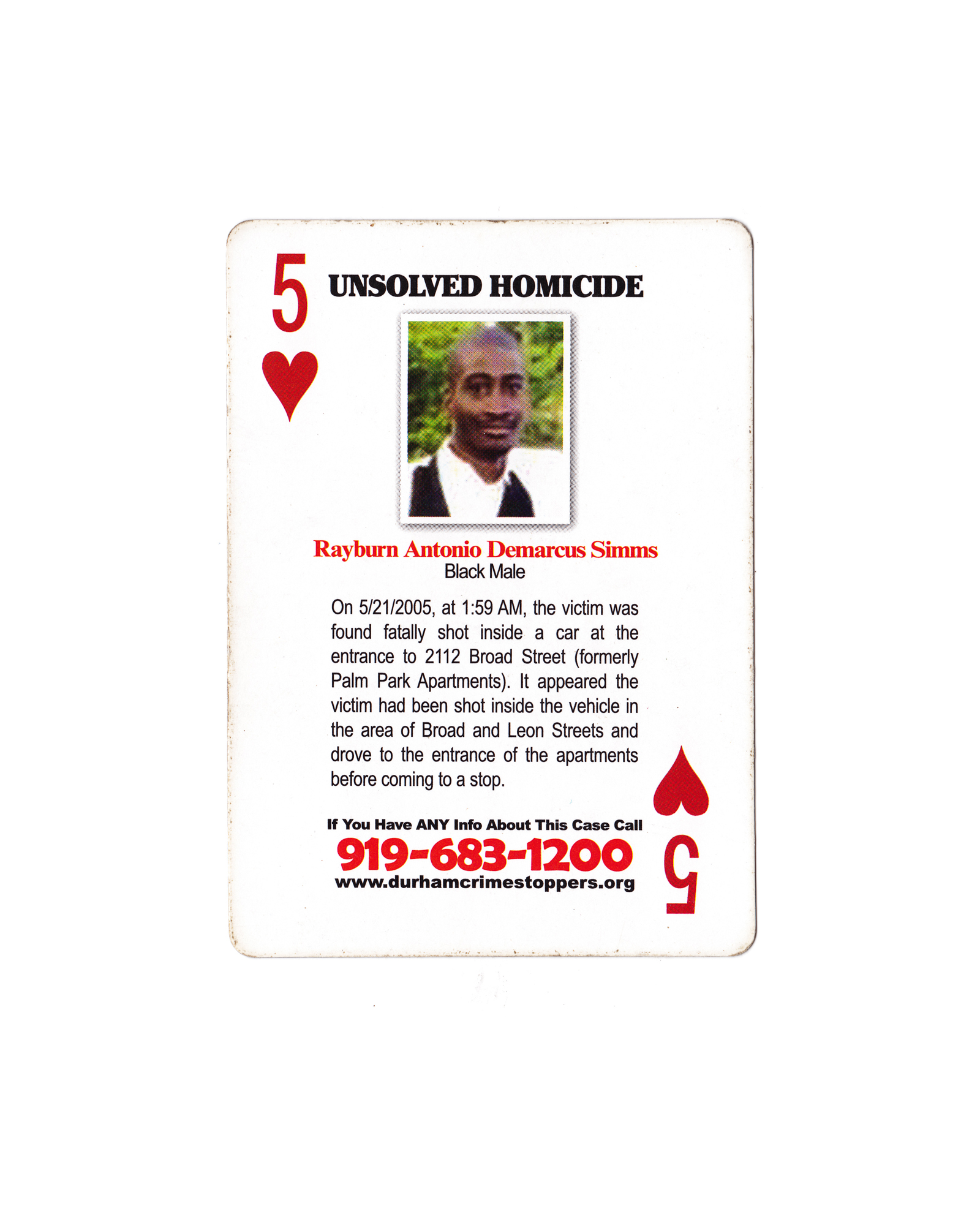

“Since Ray been murdered, I have nightmares. I dream of him in the morgue and when they are cutting his body I wake up because I can feel the knife cutting me,” says Joslin Simms, who weeps at the corner of Broad and Leon streets where her son, Rayburn, 30, was shot to death on May 21, 2005. The case remains unsolved. Ray left behind four children and a devastated mother. A decade later, Joslin limps along maimed by grief and depression. She calls it a “walking death.”

“I just want to go dig up his body so I can touch his face one more time,” says Joslin at her son’s grave in Beechwood Cemetery, in 2007. Her imagination leaves her restless. She sees Ray’s face on the young men walking down her street; “Ray! Ray!” she calls out to them, but when she blinks, their features morph, and suddenly they aren’t him.

Gang graffiti near the intersection of Vale and Clay streets in 2005. East Durham’s Census Tract 10.01 is 67 percent African-American, has a 45 percent poverty rate, a 19 percent unemployment rate, and a per capita annual income of $10,126 according to U.S. Census American Community Survey 2013 five-year estimates. Nationally, two-thirds of people in jails report annual incomes below $12,000 prior to arrest. DATA SOURCE: RACHEL L. MCCLEAN AND MICHAEL D. THOMPSON, REPAYING DEBTS (2007).

On house arrest for failing to pay his restitution, Rashard Johnson is afraid to set off his monitoring anklet, so he keeps one foot in the house while he smokes a cigarette in 2012. Rashard never knew his dad, and his mother did the best she could to make ends meet. He ran away from home, and at 16 he was arrested and charged as an adult for breaking into houses and possession of stolen goods. By 18, he was convicted of many nonviolent felonies. In 2012, when this image was taken, he had escaped gang life. He wanted to start over, and use his past to help other young black men. But Rashard’s felonies follow him wherever he goes. These convictions make it difficult for ex-offenders to find a job, a place to live, to get an education and live a stable life. How will Rashard become more than his past if he is perpetually punished for his mistakes? North Carolina and New York are the only states that still prosecute 16-year olds as adults in felony cases. Durham recently passed an initiative banning the check box on employment applications that ask whether the applicant has been convicted of a crime or been incarcerated.

Young men who identify as Crips gather in a circle and spill liquor to mourn Maurice Streeter, who was shot and killed in April 2013. Neighborhood cliques and gangs offer young people a sense of purpose and family in neighborhoods torn apart by poverty and incarceration. The drug markets they often enforce are a substitute for a mainstream economy, which they are excluded from.

Gloria Streeter’s funeral, August 2014. Gloria died after complications from a stroke. Her son, Maurice, was killed in April 2013. Her family says she never got over her son’s death, and a broken heart contributed to her demise.

Mothers of murder victims and memorials to the slain in Durham.

Crosses from a memorial to homicide victims stacked inside The Shepherd’s House United Methodist Church in East Durham in 2013. Shepherd’s House is dedicated to nonviolence and reconciliation.

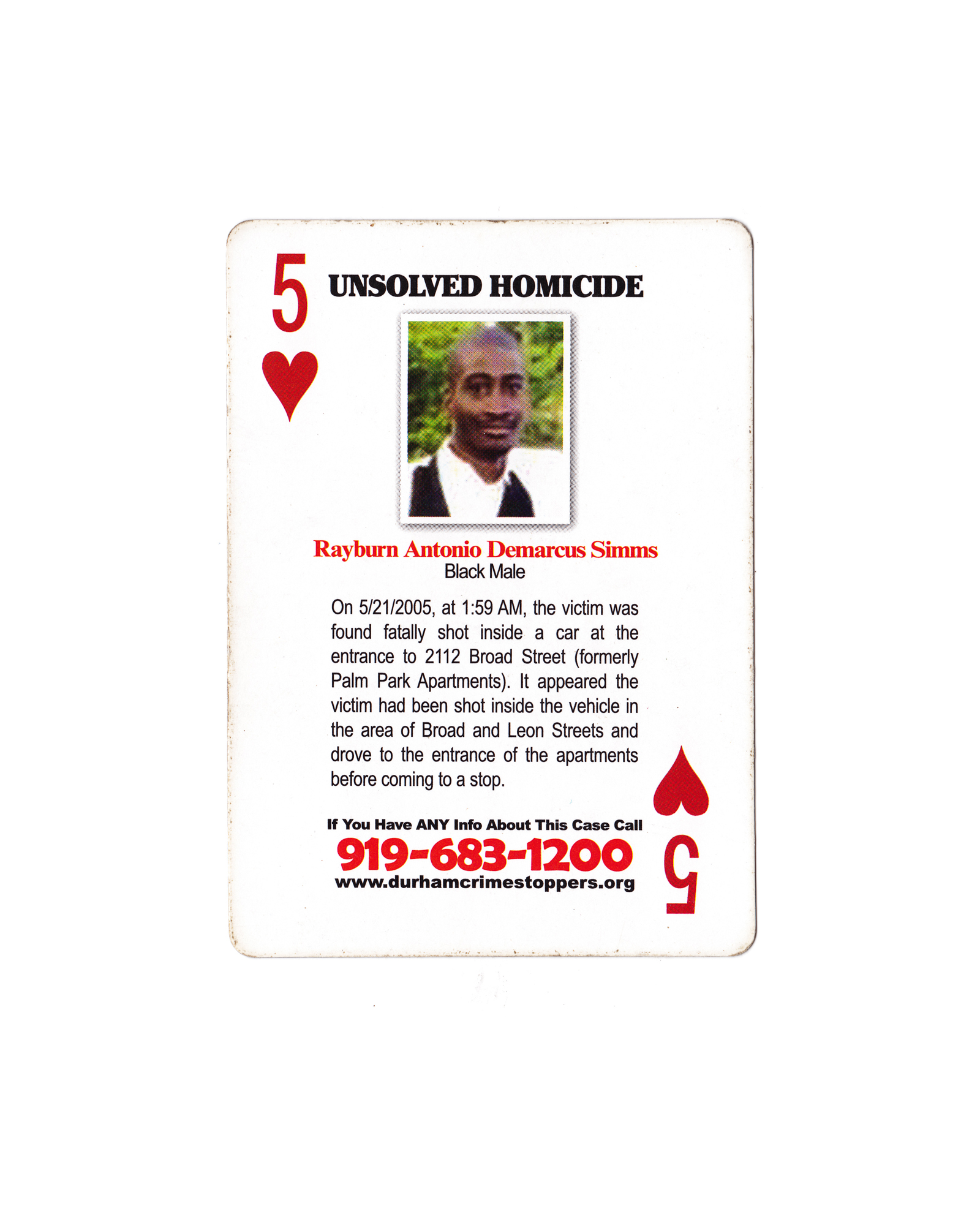

Rayburn Antonio Demarcus Simms is featured among 51 other unsolved Durham homicides in a deck of playing cards designed to generate leads in cold murder cases. According to Durham Police, there are more than 150 unsolved homicides in Durham stretching back to the 1990s. Distrust of the police and fear of retaliation for snitching discourages many African-American witnesses from coming forward, and prevents murders from being solved.

The remains of Fayette Place public housing project on Fayetteville Street in 2011. The 20-acre property, which used to be home to low-income families, has been vacant since 2007. The property was purchased by a developer that planned to turn it into affordable housing for N.C. Central University students. But by 2015, nothing has been done with the property where 200 apartments once stood. There is an acute affordable housing shortage in Durham County, and fewer low-income, working-class families can find a home. There are 8,358 total subsidized units in the county, but only 111 available according to Durham County Open Data from February, 2015.

After a drug raid in 2005, a member of the Durham Police Department Selective Enforcement Team escorts a child to the bathroom. His mother was temporarily detained during the search of the home and couldn’t tend to him. Through raids, officers hope to recover illegal or stolen guns, and disrupt drug trafficking and gang activity. Some residents welcome the raids; others complain that they terrorize the neighborhood, and that police efforts should focus on solving murders and other violent crimes. Many SET officers have children, and none of them like it when kids are caught in the middle of drug raids.

Rashard Johnson at the Durham County Detention Center after being arrested for cutting off his house arrest ankle monitor, violating his probation, and going on the run for two months. Without a GED or a job, Rashard couldn’t repay his restitution and succumbed to frustration in 2012.

A squirt gun war breaks out before a foot race outside of Fullsteam Brewery at the edge of the gentrifying Cleveland-Holloway and Old Five Points neighborhoods in Northeast Central Durham. After a first wave of reinvestment by the City and developers, an area once riddled with vacant and abandoned homes, businesses, and lots now buzzes with energy again as a hub for creatives and foodies. The neighborhood is rapidly changing, but many wonder, ‘Into what, and for whom?’

Blood stains remain hours after a bystander was killed by a stray bullet in East Durham.

Congregants of Mount Gilead Baptist Church, led by Pastor Sanders Tate (far right), pray for peace at an East Durham intersection at the beginning of the 2013 school year.

Joslin Simms recovers at Duke University Medical Center after a stroke. The stress of her grief weighs on her constantly. A 2012 study published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry found “strokes were more common among those with stressful lives and high-strung personalities, even after controlling for risk factors like smoking and diabetes.”

Demolition and construction continues in Durham’s Southside neighborhood in 2013. Nonprofits have partnered with the City of Durham to reclaim land in the neighborhood for a redevelopment project. The goal is to build nicer and more affordable housing, and to revitalize the area. Some residents are excited about a fresh start for the neighborhood, were homes start at $160,000 and income-based subsidies are offered by the city. But other Southside residents don’t think the price is affordable and feel wary of the effects of gentrification and urban infill in their proud, historically black neighborhood. They say past urban renewal projects in Durham, including the construction of the Durham Freeway, dislocated a once centralized and vibrant black community. Many residents dub these projects “Urban Removal.” Southside’s census tract 13.01 is 77 percent African-American; 45 percent of its total population lives in poverty and 26 percent are unemployed. The annual median household income is $18,125 according to 2013 American Community Survey five-year estimates.

Rashard Johnson waits to interview at a Durham job fair that helps felons, the recently incarcerated and others with a criminal record to find employment. Rashard served nine months in prison and a judge waived his restitution upon his release. He landed a job as a door-to-door salesmen for a cable and internet company, but quit the job after a few months because he couldn’t make sales, which were based on commission. Being a felon is at once boring and agonizing. Rashard felt like he had no purpose, and he spent his days worrying and waiting. Studies estimate that one-third of young black men in the U.S. are out of work. The jobless rate for black male high school dropouts, including the incarcerated, is 65 percent. DATA SOURCE: BRUCE WESTERN, PUNISHMENT AND INEQUALITY IN AMERICA (2006).

Rashard Johnson kisses his girlfriend Cheyenne after being apart for several weeks in 2012. They eventually break up because of the instability caused by Rashard's criminal record.

Revelers gather at the Marry Durham celebration in the revitalized Central Park District in 2012. Durhamites pledged their love and commitment to the city during a mock marriage ceremony and parade.

Young men revel along Fayetteville Street during Hillside High School’s homecoming parade. Hillside has a predominantly African-American student population and serves many low-income communities in East and South Durham. According to Durham Public Schools data, Hillside once had a graduation rate as low as 52 percent in 2009, but it rose to 89 percent in 2014.

The 64th annual Watts-Hillandale Neighborhood Independence Day Parade at Oval Park in west Durham. Watts-Hillandale's census tract 4.01 is 82 percent white. Only 8 percent of people live in poverty and 94 percent graduated high school; only 4 percent are unemployed and the per capita income is $35,016 according to U.S. Census American Community Survey 2013 five-year estimates.

A man who calls himself "Lil' Salt" flexes in triumph after climbing the corner store dressed as Spider-Man during Halloween festivities in Durham's Southside neighborhood. The Southside has endured despite violence in the past decade, but is changing rapidly under the City of Durham's redevelopment plans.

Z'Dayvia Holloway, 7, dressed as Snow White, posed for a portrait at the Southside Community Center on Halloween in 2014.

Ray’s brother Billy Simms remembers his slain brother as friends and family celebrate Ray's birthday in 2012, seven years after his murder. Billy said he used to sell drugs and live the street life, but gave it all up when Ray was killed. Now he works in a mechanic shop. “I used to make $1,000 a week, but I was always afraid. Now I barely make a dime, but I got a lot more joy,” he says.

Durham Police officer R. Carson dances with members of North Carolina Central University’s step dance team during National Night Out near McDougald Terrace, a low-income public housing project where shootings have been

frequent. National Night Out events strengthen relationships between neighborhoods, civic groups, and police in an effort to fight crime and increase community spirit. Only about 42 percent of Durham Police officers live in Durham, according to a 2014 city report. The late Harvard University criminal justice scholar William Stuntz saw a cure to violent crime through a return to neighborhood-friendly policing over modern proactive, militaristic methods. Encouraging officers to live in or near the neighborhoods they patrol builds trust, discourages crime, and makes witnesses feel safer to talk when violence occurs. The results are more effective jury trials, fewer plea deals, more respect for the police, and more democratic justice in communities that struggle with poverty and violence.

Rashard Johnson’s crucifix after a job fair for felons. In his lowest moments, Rashard finds refuge in his faith.

In 2015, Rashard helps demolish and renovate an old restaurant into a new coffee shop in Durham. He began to piece his life back together as he worked on a construction crew with New Beginnings, a faith-based nonprofit that helps the recently incarcerated find work and stability. Most people with felony records are limited to construction and manual labor.

Community is formed from grief as mothers laugh and weep when they remember their murdered sons and daughters during a meeting of the Circle of Hope and Healing. The meetings are held for grieving parents by The Religious Coalition for a Nonviolent Durham in the basement of The Shepherd’s House United Methodist Church in East Durham.

A community vigil for Jeremy Turner, who was shot to death on May 17, 2011, when he was 19 years old. About 100 friends and family gathered on July 17, 2013, at the family home on Gerard Street to celebrate what would have been Jeremy’s 22nd birthday. The Religious Coalition for a Nonviolent Durham holds vigils at the site of homicides in Durham as a call for peace, community unity, and healing.

Shae Simms gave birth to a son, Bryson DeMarcus China, named after her murdered father Rayburn Antonio DeMarcus Simms, at Duke Regional Hospital in Durham in July 2014.

Raven Simms, Ray’s daughter, shows off her prom dress to her grandmother, Joslin, and her mother, Sheila, in 2013. Raven and her siblings miss Ray the most on holidays, birthdays, proms, graduations, and other milestones. She says her father came to her in a dream a week before her senior prom. He held her tightly, whispered to her that he loved her and that everything was going to be all right. Then he vanished back to his grave.

Joslin Simms poses with politicians and gun-control advocates after speaking at a Mayors Against Illegal Guns rally in Chapel Hill in 2014. Increasingly isolated by depression and grief, Joslin found companionship and community in organizations like Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense. She and other mothers who have lost their children to violence don’t want them to have died in vain, so they have organized with the hope of influencing national and local gun, education and anti-poverty policies.

Rashard looks across a quad at Howard University in Washington, D.C. after speaking about his incarceration experience. He dreams of being a motivational speaker, and in 2015 was making steps towards that dream.

A summer storm rolls in over Angier Avenue and Driver Street in East Durham at sunset.

Made in Durham the zine, front cover.

Fireworks burst over the Durham Bulls Athletic Park in revitalized downtown Durham, N.C. on Independence Day, July 4, 2014.

A mural of Durham’s historic African-American Hayti Community at the Heritage Square shopping center is disintegrating. Older residents say Hayti was ruined in the 1960s and 1970s by urban renewal projects including the Durham Freeway, which cut off thriving black businesses from downtown. Others suggest that Hayti was already declining through unemployment and people leaving the neighborhood and that its demise was inevitable.

Kalin Swinney pauses by the casket of his first cousin, 9-year-old Jaeden Sharpe, at Beechwood Cemetery. Jaeden was shot in the head and his mother, in the face, as they sat in her car near their home on Jan. 4, 2014. He died Jan. 9. His murder was the first of 2014 in Durham. Nationally, the leading cause of death for black males ages 15 to 34 is homicide, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. From 2009 to 2012, Durham’s homicide rate for black males ages 15 to 34 was about eight times the national rate. Seventy-three percent of gun-homicide victims ages 15 to 34 were black; 3 percent were white. Eighty-three percent of gun-involved aggravated assault victims were black; 8 percent were white, according to an April 2015 U.S. Department of Justice report.

“Since Ray been murdered, I have nightmares. I dream of him in the morgue and when they are cutting his body I wake up because I can feel the knife cutting me,” says Joslin Simms, who weeps at the corner of Broad and Leon streets where her son, Rayburn, 30, was shot to death on May 21, 2005. The case remains unsolved. Ray left behind four children and a devastated mother. A decade later, Joslin limps along maimed by grief and depression. She calls it a “walking death.”

“I just want to go dig up his body so I can touch his face one more time,” says Joslin at her son’s grave in Beechwood Cemetery, in 2007. Her imagination leaves her restless. She sees Ray’s face on the young men walking down her street; “Ray! Ray!” she calls out to them, but when she blinks, their features morph, and suddenly they aren’t him.

Gang graffiti near the intersection of Vale and Clay streets in 2005. East Durham’s Census Tract 10.01 is 67 percent African-American, has a 45 percent poverty rate, a 19 percent unemployment rate, and a per capita annual income of $10,126 according to U.S. Census American Community Survey 2013 five-year estimates. Nationally, two-thirds of people in jails report annual incomes below $12,000 prior to arrest. DATA SOURCE: RACHEL L. MCCLEAN AND MICHAEL D. THOMPSON, REPAYING DEBTS (2007).

On house arrest for failing to pay his restitution, Rashard Johnson is afraid to set off his monitoring anklet, so he keeps one foot in the house while he smokes a cigarette in 2012. Rashard never knew his dad, and his mother did the best she could to make ends meet. He ran away from home, and at 16 he was arrested and charged as an adult for breaking into houses and possession of stolen goods. By 18, he was convicted of many nonviolent felonies. In 2012, when this image was taken, he had escaped gang life. He wanted to start over, and use his past to help other young black men. But Rashard’s felonies follow him wherever he goes. These convictions make it difficult for ex-offenders to find a job, a place to live, to get an education and live a stable life. How will Rashard become more than his past if he is perpetually punished for his mistakes? North Carolina and New York are the only states that still prosecute 16-year olds as adults in felony cases. Durham recently passed an initiative banning the check box on employment applications that ask whether the applicant has been convicted of a crime or been incarcerated.

Young men who identify as Crips gather in a circle and spill liquor to mourn Maurice Streeter, who was shot and killed in April 2013. Neighborhood cliques and gangs offer young people a sense of purpose and family in neighborhoods torn apart by poverty and incarceration. The drug markets they often enforce are a substitute for a mainstream economy, which they are excluded from.

Gloria Streeter’s funeral, August 2014. Gloria died after complications from a stroke. Her son, Maurice, was killed in April 2013. Her family says she never got over her son’s death, and a broken heart contributed to her demise.

Mothers of murder victims and memorials to the slain in Durham.

Crosses from a memorial to homicide victims stacked inside The Shepherd’s House United Methodist Church in East Durham in 2013. Shepherd’s House is dedicated to nonviolence and reconciliation.

Rayburn Antonio Demarcus Simms is featured among 51 other unsolved Durham homicides in a deck of playing cards designed to generate leads in cold murder cases. According to Durham Police, there are more than 150 unsolved homicides in Durham stretching back to the 1990s. Distrust of the police and fear of retaliation for snitching discourages many African-American witnesses from coming forward, and prevents murders from being solved.

The remains of Fayette Place public housing project on Fayetteville Street in 2011. The 20-acre property, which used to be home to low-income families, has been vacant since 2007. The property was purchased by a developer that planned to turn it into affordable housing for N.C. Central University students. But by 2015, nothing has been done with the property where 200 apartments once stood. There is an acute affordable housing shortage in Durham County, and fewer low-income, working-class families can find a home. There are 8,358 total subsidized units in the county, but only 111 available according to Durham County Open Data from February, 2015.

After a drug raid in 2005, a member of the Durham Police Department Selective Enforcement Team escorts a child to the bathroom. His mother was temporarily detained during the search of the home and couldn’t tend to him. Through raids, officers hope to recover illegal or stolen guns, and disrupt drug trafficking and gang activity. Some residents welcome the raids; others complain that they terrorize the neighborhood, and that police efforts should focus on solving murders and other violent crimes. Many SET officers have children, and none of them like it when kids are caught in the middle of drug raids.

Rashard Johnson at the Durham County Detention Center after being arrested for cutting off his house arrest ankle monitor, violating his probation, and going on the run for two months. Without a GED or a job, Rashard couldn’t repay his restitution and succumbed to frustration in 2012.

A squirt gun war breaks out before a foot race outside of Fullsteam Brewery at the edge of the gentrifying Cleveland-Holloway and Old Five Points neighborhoods in Northeast Central Durham. After a first wave of reinvestment by the City and developers, an area once riddled with vacant and abandoned homes, businesses, and lots now buzzes with energy again as a hub for creatives and foodies. The neighborhood is rapidly changing, but many wonder, ‘Into what, and for whom?’

Blood stains remain hours after a bystander was killed by a stray bullet in East Durham.

Congregants of Mount Gilead Baptist Church, led by Pastor Sanders Tate (far right), pray for peace at an East Durham intersection at the beginning of the 2013 school year.

Joslin Simms recovers at Duke University Medical Center after a stroke. The stress of her grief weighs on her constantly. A 2012 study published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry found “strokes were more common among those with stressful lives and high-strung personalities, even after controlling for risk factors like smoking and diabetes.”

Demolition and construction continues in Durham’s Southside neighborhood in 2013. Nonprofits have partnered with the City of Durham to reclaim land in the neighborhood for a redevelopment project. The goal is to build nicer and more affordable housing, and to revitalize the area. Some residents are excited about a fresh start for the neighborhood, were homes start at $160,000 and income-based subsidies are offered by the city. But other Southside residents don’t think the price is affordable and feel wary of the effects of gentrification and urban infill in their proud, historically black neighborhood. They say past urban renewal projects in Durham, including the construction of the Durham Freeway, dislocated a once centralized and vibrant black community. Many residents dub these projects “Urban Removal.” Southside’s census tract 13.01 is 77 percent African-American; 45 percent of its total population lives in poverty and 26 percent are unemployed. The annual median household income is $18,125 according to 2013 American Community Survey five-year estimates.

Rashard Johnson waits to interview at a Durham job fair that helps felons, the recently incarcerated and others with a criminal record to find employment. Rashard served nine months in prison and a judge waived his restitution upon his release. He landed a job as a door-to-door salesmen for a cable and internet company, but quit the job after a few months because he couldn’t make sales, which were based on commission. Being a felon is at once boring and agonizing. Rashard felt like he had no purpose, and he spent his days worrying and waiting. Studies estimate that one-third of young black men in the U.S. are out of work. The jobless rate for black male high school dropouts, including the incarcerated, is 65 percent. DATA SOURCE: BRUCE WESTERN, PUNISHMENT AND INEQUALITY IN AMERICA (2006).

Rashard Johnson kisses his girlfriend Cheyenne after being apart for several weeks in 2012. They eventually break up because of the instability caused by Rashard's criminal record.

Revelers gather at the Marry Durham celebration in the revitalized Central Park District in 2012. Durhamites pledged their love and commitment to the city during a mock marriage ceremony and parade.

Young men revel along Fayetteville Street during Hillside High School’s homecoming parade. Hillside has a predominantly African-American student population and serves many low-income communities in East and South Durham. According to Durham Public Schools data, Hillside once had a graduation rate as low as 52 percent in 2009, but it rose to 89 percent in 2014.

The 64th annual Watts-Hillandale Neighborhood Independence Day Parade at Oval Park in west Durham. Watts-Hillandale's census tract 4.01 is 82 percent white. Only 8 percent of people live in poverty and 94 percent graduated high school; only 4 percent are unemployed and the per capita income is $35,016 according to U.S. Census American Community Survey 2013 five-year estimates.

A man who calls himself "Lil' Salt" flexes in triumph after climbing the corner store dressed as Spider-Man during Halloween festivities in Durham's Southside neighborhood. The Southside has endured despite violence in the past decade, but is changing rapidly under the City of Durham's redevelopment plans.

Z'Dayvia Holloway, 7, dressed as Snow White, posed for a portrait at the Southside Community Center on Halloween in 2014.

Ray’s brother Billy Simms remembers his slain brother as friends and family celebrate Ray's birthday in 2012, seven years after his murder. Billy said he used to sell drugs and live the street life, but gave it all up when Ray was killed. Now he works in a mechanic shop. “I used to make $1,000 a week, but I was always afraid. Now I barely make a dime, but I got a lot more joy,” he says.

Durham Police officer R. Carson dances with members of North Carolina Central University’s step dance team during National Night Out near McDougald Terrace, a low-income public housing project where shootings have been

frequent. National Night Out events strengthen relationships between neighborhoods, civic groups, and police in an effort to fight crime and increase community spirit. Only about 42 percent of Durham Police officers live in Durham, according to a 2014 city report. The late Harvard University criminal justice scholar William Stuntz saw a cure to violent crime through a return to neighborhood-friendly policing over modern proactive, militaristic methods. Encouraging officers to live in or near the neighborhoods they patrol builds trust, discourages crime, and makes witnesses feel safer to talk when violence occurs. The results are more effective jury trials, fewer plea deals, more respect for the police, and more democratic justice in communities that struggle with poverty and violence.

Rashard Johnson’s crucifix after a job fair for felons. In his lowest moments, Rashard finds refuge in his faith.

In 2015, Rashard helps demolish and renovate an old restaurant into a new coffee shop in Durham. He began to piece his life back together as he worked on a construction crew with New Beginnings, a faith-based nonprofit that helps the recently incarcerated find work and stability. Most people with felony records are limited to construction and manual labor.

Community is formed from grief as mothers laugh and weep when they remember their murdered sons and daughters during a meeting of the Circle of Hope and Healing. The meetings are held for grieving parents by The Religious Coalition for a Nonviolent Durham in the basement of The Shepherd’s House United Methodist Church in East Durham.

A community vigil for Jeremy Turner, who was shot to death on May 17, 2011, when he was 19 years old. About 100 friends and family gathered on July 17, 2013, at the family home on Gerard Street to celebrate what would have been Jeremy’s 22nd birthday. The Religious Coalition for a Nonviolent Durham holds vigils at the site of homicides in Durham as a call for peace, community unity, and healing.

Shae Simms gave birth to a son, Bryson DeMarcus China, named after her murdered father Rayburn Antonio DeMarcus Simms, at Duke Regional Hospital in Durham in July 2014.

Raven Simms, Ray’s daughter, shows off her prom dress to her grandmother, Joslin, and her mother, Sheila, in 2013. Raven and her siblings miss Ray the most on holidays, birthdays, proms, graduations, and other milestones. She says her father came to her in a dream a week before her senior prom. He held her tightly, whispered to her that he loved her and that everything was going to be all right. Then he vanished back to his grave.

Joslin Simms poses with politicians and gun-control advocates after speaking at a Mayors Against Illegal Guns rally in Chapel Hill in 2014. Increasingly isolated by depression and grief, Joslin found companionship and community in organizations like Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense. She and other mothers who have lost their children to violence don’t want them to have died in vain, so they have organized with the hope of influencing national and local gun, education and anti-poverty policies.

Rashard looks across a quad at Howard University in Washington, D.C. after speaking about his incarceration experience. He dreams of being a motivational speaker, and in 2015 was making steps towards that dream.

A summer storm rolls in over Angier Avenue and Driver Street in East Durham at sunset.